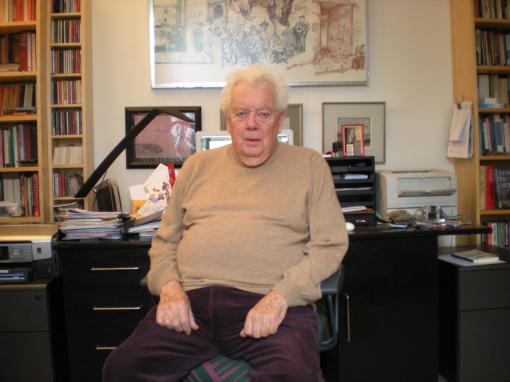

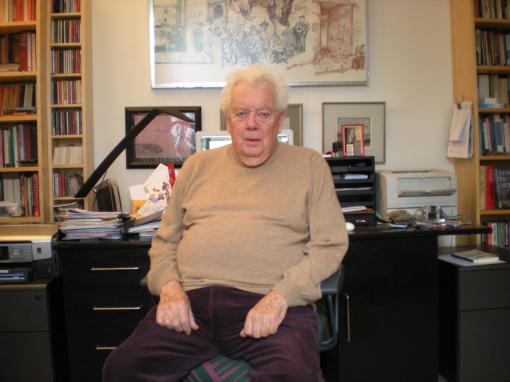

I met David Kingsley, the advertising guru who helped transform the Labour party in the 1960s. Here he talks about working for Harold Wilson, how it feels to be compared to Alastair Campbell, and whether he thinks Gordon Brown can beat David Cameron at the next election.

A small box sits on the mantelpiece in the study, a slogan playfully scrawled across its side in marker pen.

.

‘Fidel Castro gave this cigar to Harold Wilson,’ it records. ‘H.W. then gave it to D.K. at a meeting on the evening of his son Andrew’s birthday.’

.

Next to the cigar case is a black and white photograph. It shows three men flanking Wilson, the tough-talking Labour prime minister whose mercurial personality dominated the politics of the 1960s. They appear to be smiling in modest celebration.

.

“Won two, lost one,” David Kingsley chuckles, nodding at the picture. Now approaching his 80th birthday, he allows himself the indulgence of raising a bushy eyebrow. He is talking, of course, about general elections. Kingsley’s natural aversion to boastfulness must be one of the reasons his story has remained one of the untold tales of modern politics, until now.

.

Before Alastair Campbell and Peter Mandelson refashioned the Labour party into an election winning machine, before ‘spin’ entered the daily lexicon of British newspapers, even before Margaret Thatcher paid two brothers from Baghdad to design her first election poster, a team of elite executives became the first professionals from the world of marketing to help a politician break into Number 10.

.

.

‘Let’s Go With Labour’ and ‘You Know Labour Works’ were the motifs that powered Harold Wilson’s Labour party to two consecutive general election victories in 1964 and 1966, accompanied by innovative TV broadcasts. They sprang from the fertile mind of a young media guru who felt his socialist leanings tugging more urgently than his wallet.

.

At the age of 33, David Kingsley was already a veteran marketeer with his own business and experience of working in New York for Proctor & Gamble, the founders of modern advertising. He was “something of a man-about-town”, he remembers with a laugh, a dynamic figure who made regular TV appearances and knew the power players in London’s blossoming advertising scene. Like Alastair Campbell, Kingsley was – and still is – a dyed-in-the-wool Labour supporter.

.

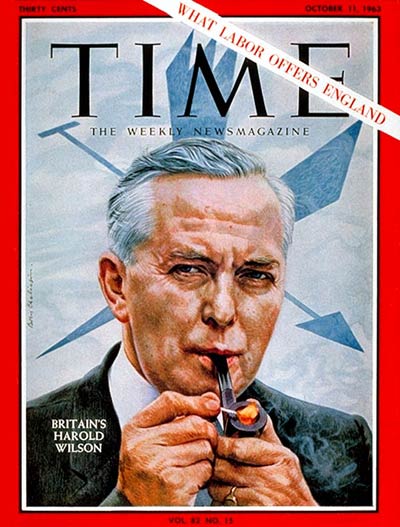

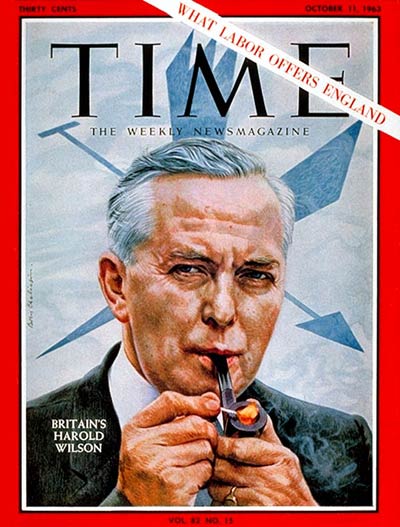

Excitement was buzzing in the air when Harold Wilson shaped up to fight the ageing Harold Macmillan in 1964. Here was an energetic challenger, fresh and full of self-belief, who promised to forge a new Britain in “the white-hot heat of technology”.

.

So when a mutual friend told him the prospective prime minister was considering radically changing the Labour party’s election strategy, Kingsley jumped at the chance to help.

.

“I had a feeling that politicians weren’t very good at communicating with the people, and the people found it very difficult to understand what the politicians were doing,” Kingsley says.

.

“The Labour party didn’t know how to communicate with words. If you look back, none of the parties really did.

.

“I became very interested in how one could use the latest marketing techniques to understand how you needed to get through to people, instead of just throwing out headlines.”

.

After Labour won the 1964 election with a slender majority, Kingsley persuaded Wilson to let him bring in two more high-flyers from the advertising realm, Peter Lovell-Davis and Denis Lyons. Together they became known – only partly in jest – as the prime minister’s Three Wise Men. The first golden age of Labour PR had truly begun.

.

“We quickly became very involved,” recalls Kingsley. “Every second Tuesday we’d go to Number 10 and chat over what was happening. Sometimes we’d find ourselves in the embarrassing situation of carrying messages from Number 10 to the party because they didn’t always see eye to eye. It was an extremely interesting period.”

.

Political folklore has it that the trio of Mandelson, Campbell and Blair were the first senior figures within the party to really hook themselves to the addictive potion of opinion polling, the gauge of public favour widely seen to be responsible for forming many of New Labour’s early policies.

.

But Kingsley insists it was the Three Wise Men – together with their friend Bob Worcester, who later went on to found the hugely successful research company Mori – who started using regular opinion polls to guide party strategy. It was they, years ahead of Tony Blair’s watershed moment, who identified the potential appeal of ditching the Labour party’s manifesto commitment to nationalisation. At the time, even raising the idea would have been like uttering a blasphemy. It was quickly shelved.

.

“They weren’t doing proper [opinion poll] research when we arrived,” Kingsley explains. “What they liked was to show their ratings once in a while, but they weren’t digging deeper to find out why people had views on things.

“So the research part of it was very important. In fact to my mind, introducing the Labour party to proper opinion poll research was one of the most important things we did.”

.

For a moment he looks slightly rueful.

.

“Bob [Worcester] was very good. If they’d used him more we needn’t have lost the 1970 election. I know everyone always looks back, but he was tracking very clearly what was happening and what the problems were in a way the Labour party had never experienced before.”

.

It’s clear the art of spin, now so associated with vicious briefings and irresponsible hype, was governed by a certain gentlemen’s code in the 1960s. Kingsley describes Wilson as “a marvellous chap” who would bring his wife and children to parties and would charm friends and foes with his bluff northern manner. He takes pains to point out that even at the peak of the Wise Men’s activities, advertising was seen as a precursor to real discussion.

.

.

“The most notorious slogan we ran against the Conservatives was ‘Yesterday’s Men’,” Kingsley says, referring to the controversial campaign that portrayed Ted Heath’s team as puppets languishing in the dustbin of history.

“But that was actually planned as a preliminary to clarifying our position. It was a preliminary to talking. I always believed you should talk about your policies and your principles, because those are the key ingredients which other people tend to feel good about or not.

.

“Things go wrong in politics when people think they know it all, when they aren’t actually closely in touch with what’s going on around them or what people feel like. But everything goes so quickly these days. We used to have time to think about these things. Now you have to think on the spot for 24-hour news.”

.

Kingsley parted amicably from the Wise Men and the Labour party when Ted Heath’s Tories scraped to power in 1970. He says he has never been tempted to return to the heart of British politics, preferring to split his time between charity work and advising a number of African governments.

.

He still takes an interest in the Labour party’s fate, though. What are his thoughts on Gordon Brown’s chances at the next ballot box? There is a long, meditative pause as Kingsley rubs his hands together.

.

“Well,” he offers, “when the first troubles came to the Labour party, and MPs were beginning to say ‘We must get rid of Brown’, I wasn’t of that ilk. We didn’t know what was going to happen, but I thought he’d come through very well at the right moment, and…”

.

Again Kingsley hesitates, weighing his words carefully.

“And, I think he has. It doesn’t mean he’s done everything right or everything wrong. But I still think he is the right person for this time. You can’t just go by what the newspapers say.

.

“There’s still a lot going to happen in the next 18 months or so until there’s an election. I think it’ll swing back to Labour, more than anything because Cameron and his crew seem to be so bad at doing things.”

.

At this point Kingsley raises his hands in mock incredulity.

.

.

“They don’t ever seem to get anything right. I’d love to advise them how to do things because it would be very easy. What is amazing is the Conservative party hasn’t yet managed to modernise itself in the sense of being a party that cares for the whole country – they just haven’t done it.”

.

Asked whether he sees the likes of Alastair Campbell and Andy Coulson as his progeny, Kingsley is more evasive. He is grateful to Peter Mandelson for breathing life back into the Labour party in the 1980s, he says, and he recognises a certain parallel between the professionalism the Three Wise Men brought Harold Wilson and the professionalism New Labour’s modernisers brought to the party 30 years later. How about Blair himself?

.

“I will always praise Tony Blair for getting the party into the frame of mind where it realised it needed to win something,” Kingsley says slowly. “Of course, many of us lost faith with the Iraq war and… it deteriorated after that.”

Silence settles for a few seconds. An email pings softly on the laptop behind him.

.

“He did a very good job for the party,” Kingsley finally pronounces. “But he was a bit of a disappointment. As a person.”

.

As the conversation draws to a close, Kingsley lets slip a surprising revelation: he didn’t draw a penny in salary from the government in all his time as its communications maestro. Offering his services for free gave him a feeling of distance from the political machine, he says, and the freedom to do as he liked. His only remuneration came in the form of a Havana cigar, itself a gift from Fidel Castro to Harold Wilson.

.

“I’ve promised to give it to one of my sons, but it’s probably falling to pieces,” he explains, gesturing towards the box on the mantelpiece. “I know the exact date Wilson gave it to me because my first son was born earlier in the evening, so I arrived at Number 10 late from the hospital.

.

“He had it ready for me, and I said, ‘I don’t smoke’. He said, ‘David, you don’t have to smoke this, but do have it as a celebration of your son’.”

.

Kingsley smiles at the memory. “I keep meaning to give it to Andrew, but I think perhaps we ought to frame it or something.”